By Cynthia R. Walker, CEO

At the time of the Great Depression, most home mortgages were short-term. The common term was three to five years, with no amortization, interest-only payments with a balloon at the maturity. Loan-to-value ratios were also below sixty percent. These terms contributed to the high rate of default during the Depression. Since that time, the mortgage industry has evolved and changed through regulation, industry, and consumer influence to modify loan terms, rates, and payment structures, thereby increasing the number of people who could afford a down payment and monthly debt service on a home.

According to the Census Bureau, in 1940, the median home value adjusted for inflation was $30,600. Now, as the average amount financed for a new auto is very close to $30,000, 84-month loan terms are becoming more common. As we know, people shop for vehicles largely based on the monthly price. Therefore, pressure mounts to increase the terms to keep the monthly payment in an affordable range. According to the OCC Semi-annual Risk Perspective published in the fall of 2015, banks are easing underwriting standards and terms, particularly in auto lending to remain competitive.

A Mortgage for Your Car?

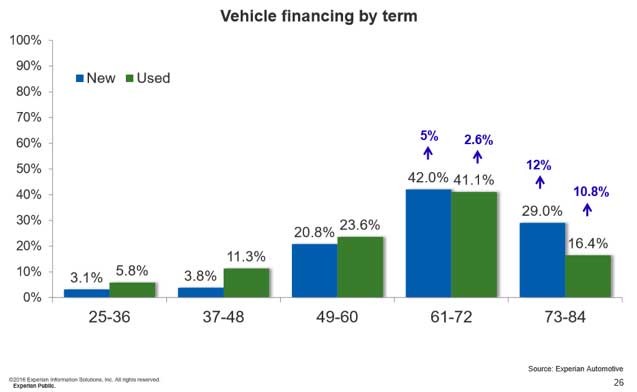

Experian’s State of the Automotive Finance Market for the Fourth Quarter of 2015 reports the average length of new and used auto loans is 67 and 63 months, respectively. The percentage of new vehicle loans with terms of 73 to 84 months grew by 12% in Q4, reaching nearly 30% of originated new vehicle loans. Similarly, the percentage of used vehicle loans with comparable terms grew by 10.8%, and represents over 16% of used vehicle loans. With the extension of loan maturities and higher loan-to-value levels, there will be increased risk in loan losses due to loan balances exceeding collateral values for a longer period of time. Another risk that should be considered in this trend is the potential for an increase in interest rate risk.

With new and used auto loans in the credit union industry up by 16% and 12.7% during the last year, it may be time for credit union management and the ALCO to evaluate lending practices, trends, and assumptions used in the interest rate risk analysis.

We recommend you consider some of the following items:

- How has the credit union’s loan portfolio and loan mix changed in the last year or two?

- Are we making longer-term automobile loans?

- Are the auto loans with the longer terms starting to represent a material percentage of the credit union’s assets?

- Should these loans be identified into their own loan category to better understand the credit union’s exposure to both interest rate risk and loan losses?

- Are the longer-term loans priced to compensate for increased risk?

- Are there other reasons to identify and model these longer-term auto loans separately?

- Has the credit union’s overall loan turnover lengthened in the last couple of years?

- Have the assumptions been reviewed and adjusted in the IRR analysis to reflect this trend?

- Has the net interest margin improved with the increase in auto loans?

- Does the increase in net interest margin offset some of the potential risks?

These are a few items to consider and discuss with the ALCO and document in the ALCO meeting minutes. Mortgage loans and long-term investments have been highly scrutinized as a source of interest rate risk. As the consumer auto loan terms extend, this could also become a source of risk on several fronts that should not be ignored. The best approach is to identify the longer-term auto loans and make sure the potential interest rate risk is measured, managed, and monitored.

In today’s environment of diminished net interest margins, with many analysts expecting they will continue to compress, structuring the balance sheet for earnings in 2016 is imperative. The longer-term auto loans may be an acceptable strategy as long as these loans are priced appropriately for the inherent risks. Loan, investment, and funding mix should focus on actively managing and achieving any and all incremental increases in net interest margin. While we spend a great deal of time anticipating the impact of hypothetical interest rate increases and structuring our balance sheets to reduce potential IRR, credit union’s should focus on maximizing their net interest margin in any rate scenario. The proverbial trick of balancing risk and return still applies.